On this page, you will learn who can represent your company. The gist of it is that a company is a separate legal entity from the persons contributing to the company. However, a company cannot act by itself, but only through a human being. A distinction is made between human beings who are considered to be the company, and those who are agents who act on behalf of the company.

Who is the Company?

Every company has two organs, namely the members and the board of directors, and either of these organs can be the Company. The memorandum and articles of association (M&A) of the company will divide the powers of the company between the general meeting (held by the members) and the board, and the Act also assigns certain powers to each organ. Within their respective spheres, as delimited by the memorandum and articles and Act, the general meeting and the board are the Company. If the members pass a resolution (within their competence) at a general meeting, that resolution represents a decision of the Company, and similarly, a resolution passed by the board , that resolution may be taken to be the decision of the Company. Their acts are the acts of the Company and not on behalf of the company – meaning there is no question of agency. Realistically however, it cannot be expected that a company can run its business with every business decision having to be decided by a committee, and as such, an agent may be given the authority to take everyday business decisions.What is an Agent?

An agent, at the most basic level, is someone who acts on someone else’s behalf and has the power to affect the legal position of that person. Agency is defined as:the relationship that exists between two persons when one, called the agent, is considered in law to represent the other, called the principal, in such a way as to be able to affect the principle’s legal position in respect of strangers to the relationship by the making of contracts or the disposition of property.”The agent is responsible for negotiating, concluding and sometimes executing (in the name of or on behalf of the company) the contract, but he is typically not personally bound by the concluded contract between his principal and the third party. Provided the agent acts within his authority, any recourse the third party has under the contract, will be against the principal not the agent.

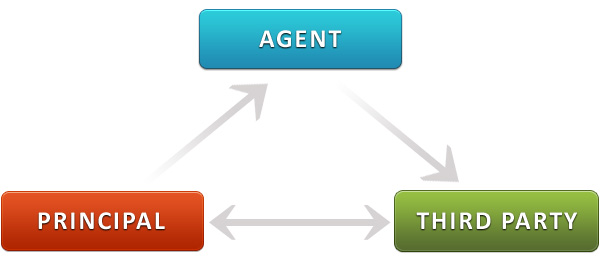

Agency creates a triangular relationship. The agent binds the principal and the third party. Normally, the third party is aware that the agent is acting on behalf of someone else. However, even if the third party is unaware that the agent was in fact acting on behalf of a principal, the principal still has the right to enforce the contract against the third party.

Agency creates a triangular relationship. The agent binds the principal and the third party. Normally, the third party is aware that the agent is acting on behalf of someone else. However, even if the third party is unaware that the agent was in fact acting on behalf of a principal, the principal still has the right to enforce the contract against the third party.

Principal – Agent Relationship

The agent must act as stipulated in the contract and has an obligation to act with reasonable care and diligence. The agent has fiduciary obligations towards his principal. The agent has a duty not to put himself in a position where his duties conflict with his personal interests.Agent – Third Party Relationship

Generally, the agent who has contracted on behalf of the principal owes no liability to the third party, nor does he have any rights against the third party.How does an Agency relationship arise?

Typically, agency may arise by express or implied authority, or by ostensible or apparent authority.Express or Actual Authority

Express authority is that which is expressly conferred upon the agent either orally or in writing. Express authority may be conferred in several ways, for example:- Memorandum or articles of association may confer authority upon a particular agent.

- The general meeting or board of directors may appoint agents and delegate duties and functions to them. For example, a resolution can be passed authorizing the Managing Director to enter into various commercial and business transactions.

- The company’s agents may delegate their authority to sub-agents.

- May be derived from the terms of a contract. For example, the employment contract for a sales rep may expressly stipulate that the rep may enter into specific transactions on behalf of the company.

- By Statute.

Implied Authority

Implied authority is not expressly stated but rather, it is authority implied by the circumstances. This may take several forms:- Incidental Authority – An agent has authority to do things incidental to the fulfillment of the tasks that he is expressly authorized to do, i.e. this would typically be something that is required in order to perform the actual task.

- Usual Authority (common in a corporate context) -The appointment of a person to an executive post impliedly authorizes him to do whatever is within the usual scope of that office. The reason for this is that it can’t be expected that every situation where the executive requires authority be specifically identified, but rather the MD has overall authority to bind the company, so long as it’s within the scope of his position and that he acts in good faith and in the furtherance of the business.

- A corporate agent may be given implied authority by the acquiescence of his superiors.

Proving implied authority

- Incidental authority – First, what the agent was expressly authorized to do must be proven, then it must be shown that what the agent did was reasonably incidental.

- Usual authority – Here the question is whether an agent in that position would reasonably be expected to have authority.

- Authority by acquiescence – It must be proven that the agent had been implicitly allowed to do what he did by his superiors. The fact that he had done similar things in the past with their tacit approval would be considered.

- Depending on the way the company is set up and run, this may infer that he has implied authority to bind the company.

Ostensible or Apparent Authority

In addition to actual authority, an agent may have ostensible authority to bind his principal. This is the authority that the agent appears to the outside world to have because of the acts of the principal. Therefore, this is the authority the agent appears to have but in fact doesn’t.- There must be a representation by the company to some person that the agent in question has the authority to do the act in question.

- The representation must have been made by someone who has authority to make such representations on behalf of the company.

- The person who wishes to enforce the contract against the company must have relied on the representation.

- Was the transaction within the authority (express or implied) of the agent?

- If so, the company is bound by the transaction. If not, consider the next question.

- Was the transaction within the apparent or ostensible authority of the agent?

- If not, the then company is not bound by the transaction. If so, then the next question arises.

- Was there anything to put the third party on notice? If so, then the company is not bound. If not, then the company will likely be bound.